silent power

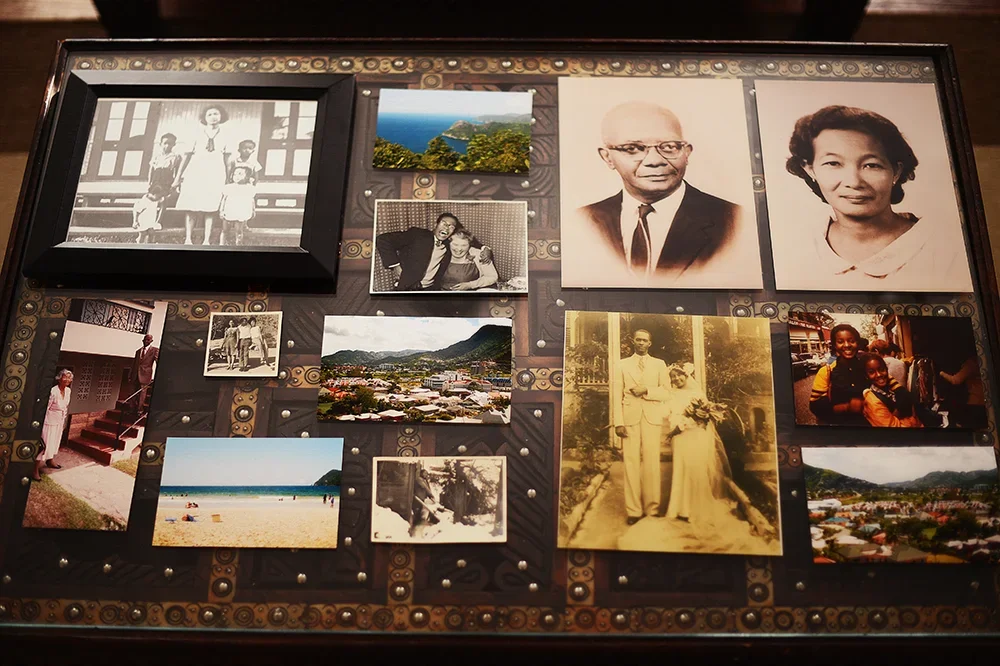

My paternal grandfather (portrait, upper right) and my maternal grandmother (the bride in the image below his): the poets.

My father’s brother —

the one who lives on a small island in a chilly ocean

thousands of miles from our homeland —

was going through his late father’s papers

(receipts, accounts, letters,

and artifacts of an early twentieth-century colony)

when he came across a poem

scrawled in my grandad’s steady hand.

The last line read:

The mightiest force in the world is the silent power of love.

I mentioned the poem to my mother,

and her eyes danced with fond memories of her father-in-law,

until suddenly, they didn’t.

”Somewhere, I have a journal of poems your grandmother wrote,”

she said, surprised at the recollection.

”I wonder where it is?”

she asked,

as if I knew.

I couldn’t answer.

I was too busy marveling

that two grandparents,

on either side of my family,

wrote poetry

in their personal papers,

quietly.

Privately.

Did everyone write poetry

in our tropical, colonial home

in the early twentieth century?

Was it common

to write in verse

to make sense

of an ever-changing, confounding world?

And if so, did they write of mighty forces of love

with conviction,

or hope?

Then I wondered,

if my grandparents were alive today,

what poetry might they have written

of superpowers led by the merciless,

of gun violence and hate crimes,

of catastrophic wildfires and historic floods,

of anguished parents clutching emaciated children,

their bodies illuminated by the red glare

of missiles

bearing the autographs

of politicians?

How might they have made sense

of events

that reduce rational thought

to sentence fragments

and

single

words?

because artificial intelligence can’t be the only game in town.